Cattle tend to congregate in riparian zones because they provide food, water, and shade. Photo George Wuerthner

One of the biggest problems in conservation is that people do not miss what they don’t know. How many people really miss the Ivory-Billed woodpecker or Stellar’s sea lion? And I’ve found that people living in the eastern United States where nearly all the virgin old-growth forest has been cut off think that a forest of 8-inch poles is a healthy landscape.

Landscape amnesia is the loss of a memory or even an idea of what has been lost or what could be again in many instances if we stopped degrading the land.

Aldo Leopold once famously wrote that ecological awareness means one lives in a world of wounds. When I travel the West, I see wounds from the livestock industry almost everywhere I go.

Smith Fork on the Cache National Forest, Utah. Note the relict willows, wide shallow stream and trampled streambanks. This is vandalism of public lands by the livestock industry. Photo George Wuerthner

One of the important ecosystems in the West that suffers due to landscape amnesia are riparian zones. Riparian areas are the thin, green line of vegetation influenced by water found along streams, seep, and springs.

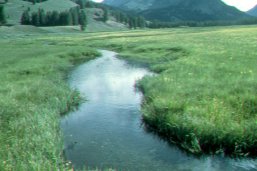

Lush cow-free riparian zone with intact vegetation and streambanks. Selway River, Selway Bitterroot Wilderness Idaho. Photo George Wuerthner

Riparian areas typically make up about 1% of the West’s vegetation, yet up to 70-80% of all wildlife species depend on them for hiding cover, nesting, and forage. They are also crucial for energy flow, nutrient cycling, water cycling, hydrologic function, and plant and animal population.

Many human activities have damaged the West’s riparian areas. Dams, irrigation withdrawals, housing, highways, and other development has altered or obliviated these fragile areas.

Cattle have totally annihilated this riparian area on BLM lands in Nevada. This should be viewed as legalized vandalism. Photo George Wuerthner

However, the single greatest impact and threat has come from livestock production. Cattle are particularly attracted to riparian areas. The majority of cattle breeds used in the West, like Black Angus and Hereford, evolved in moist woodlands in northern Europe. Consequently, they are naturally attracted to the only green, lush habitat found in many arid western landscapes that remotely resembles their ancestorial homelands.

Note the wide shallow stream and vegetation that has been grazed to golf ball height. Normally the grass in such wet areas should be a foot or more high. Sunflower Allotment, Ochoco National Forest, Oregon. Photo George Wuerthner

Riparian areas typically support the bulk of all palatable vegetation found on many grazing allotments. If you go to, say, a mountain valley in many western ranges, the hillsides are steep, and cattle avoid them, while the green grass and water pull them down into the stream corridor. Plus, riparian zones provide shade and water, two other significant attractants to domestic livestock.

The evolutionary attraction of cattle for riparian areas has dire consequences for the West’s wildlife and aquatic ecosystems.

Cow trashed riparian area on the Boise NF, Idaho. Note the stream is shallow and wide which means it provides less habitat for aquatic species and warms up faster in the sun. Photo George Wuerthner

The majority of riparian areas on public lands (and private lands) are not functioning. With heavy grazing, the riparian vegetation may be removed and banks broken down so that the stream can no longer reach its flood plain. When this happens, a stream will begin to “down cut’ to make an arroyo or deep gully. Over time, the ravine cuts farther up the creek and is known as “head cutting.”

The above photos were taken in the Sawtooth Valley, Idaho on the Sawtooth National Forest. The first photo shows a severely damaged riparian area and stream, but most people would probably think it looks like a good trout stream. But once the stream crosses the fence into an area that has had no livestock grazing for 100 years, the stream suddenly narrows and deepens. The last photo is taken about 100 feet from the fence and the stream is completely invisible. The channel is so deep and narrow with lush vegetation over it that it’s nearly impossible to see. Photos George Wuerthner

Another consequence is that riparian vegetation dependent on water disappears, and plants adapted to arid situations will establish near the creek or stream. For example, I’ve seen many places where sagebrush grows immediately adjacent to a stream. Since sagebrush cannot tolerate flooding, this is often a sign that the water table has dropped.

Healthy riparian areas also slow floodwaters and decrease erosion.

Cattle have broken down the banks of this stream, striped the riparian vegetation and compacted the soil. The Nature Conservancy ranch in Utah. Photo George Wuerthner

Cattle hooves compact soils, especially the wet soils found along streams. Soil compaction decreases water infiltration and storage. Healthy springs seep, and riparian areas are like sponges, soaking up water in the wet season and releasing it slowly in the dry season.

Thus, maintaining a healthy riparian has numerous economic values in reducing floods and supporting healthy aquatic ecosystems for fish and other wildlife.

The lush vegetation along riparian areas also provides cover for many birds and mammals. For instance, sage grouse chick move to riparian areas after they are born to feed on forbs and insects and to find cover from predators. When riparian areas are grazed down to putting green height, they provide no cover and little food for sage grouse and many other species.

Healthy riparian areas are so rare that almost everyone has landscape anemia regarding what a healthy functioning riparian zone is supposed to look like.

This is a healthy riparian area and stream in Yellowstone National Park. Note the grass is over a foot tall, with the vegetation all the way to the water and intact banks. Photo George Wuerthner

As a general rule, here are some things to look for. A healthy riparian area will be dominated by native vegetation like willow, cottonwood, red osier dogwood, and other shrubs or sometimes native grasses that require a good water supply. A healthy stream with an intact riparian zone will often access its flood plain and tends to have deep undercut banks. Damaged streams are wide and shallow.

Federal and state agencies are forced to act because of the growing public awareness of the importance of healthy streams and riparian areas. However, they tend to favor mechanical solutions rather than eliminating livestock grazing from public lands. These solutions favor the livestock industry, typically at public expense.

Rather than eliminate livestock grazing by private interests, the government often builds expensive half way solutions like tapping springs or streams and pumping the water to a water trough–all at public expense to protect the public land from ranching vandalism. Photo George Wuerthner

Sometimes the fence riparian areas to keep cattle out of the zone. However, fences are costly and need to be maintained to work. They also inhibit the free movement of other wildlife.

Fence built to protect the riparian area from livestock. Red Rock Valley, Montana. George Wuerthner

Another “solution” is to build a pipeline that transfers water from a spring or stream to a water trough some distance from the stream so that cows get the water without damaging the streambanks. However, draining springs to provide water to private cattle also impacts many animals that depend on intact springs and streams for their survival. For instance, many amphibians like frogs and salamanders tend to be found around these water sources. Not to mention water being pumped out of a spring or stream is necessary to maintain the aquatic ecosystems.

The best solution is the one that is seldom implemented: the removal of cattle from public lands. When the choice is protecting the public values or protecting the profit of private businesses (i.e., ranchers), the range cons that manage livestock on public lands nearly always favor the rancher.

The first photo of cattle grazing the San Pedro River Riparian Conservation Area in Arizona. The second photo was taken from the same photo point ten years after cattle were eliminated from the river. Landscape amnesia is the biggest obstacle to bringing about range reform. Photo George Wuerthner

The first step in changing these dynamics is to recognize the problem. Landscape amnesia is not acceptable.

Comments

Amen!!

Thank you; it is hard to believe, but true,that our public land managers (USFS, BLM. and State agencies)will not accept that cattle are attracted to and will congregate in riparian habitat. It is where they find shade, water, green vegetation. Attracting them to shadeless, dry brown vegetation. and steep ridges with water “improvements” is just not the same.

Yes, it’s true that livestock will ruin riparian areas — if they are not managed correctly. We need to distinguish between those that are allowed to freely graze and those that are controlled to allow them to restore lands that have soils that are damaged from overgrazing.

If you want to have your mind blown, read this paper about soil restoration with livestock on drought-ridden lands in the Southwest and Mexico. Turns out that when soil is restored, the land that has come alive again, actually receives 1-2″ MORE RAIN than adjacent properties. (It turns out that new evidence and research regarding the impact of soil microbes on the creation of precipitation can be characterized as a game changer in our understanding of what it takes to produce rain across the globe.”https://understandingag.com/regenerative-rainmaking/

Taking livestock off of public lands–if those lands are damaged, is the worst choice, because there is still the wrong-headed belief that such lands “just need to rest.” No. The entire ecosystem needs to be healed, and if you allow elk, for example, to roam free without predators to manage them, you’ll have the same damage.

Reminder: 70% of grasslands on the globe, which includes public lands in the US, are turning to DESERT!!!

Nature has a design that we ignore at our peril!

After reading the article, I would suggest that’s it’s more important to get cattle off the land because they are carrying antibiotics that prevent the spread of beneficial biotae. Assumably the elk would not have been antibiotics and would have ‘safe’ feces and urine, no? Just a mind exercise at this point, but I see problems with keeping -any- farm animals on land if their waste has antibiotic properties in it

The formula is not that hard to understand. If you want wildlife get rid of the cattle. If you want desert keep the cows.

What an irony. The American bison has been kicked off public lands to make room for non-native range maggot cattle and sheep. There is nothing fair or ecological about it. Don’t believe the BS.

The BLM, USFS, and now the FWS have turned into ‘paper tigers’ as far as management goes. These agencies put up their smoke screen of propaganda to keep cattle ranchers and businesses that associate with them satisfied using our tax money while trying to convince America that they are actually protecting something. Congress behind the scenes keep their feet on the necks of the agency heads to make sure they comply. Then the congress people get there “rebates” in the form of campaign contributions. It is not a good system in the least. It should be replaced.

Ask our native prairie dogs that are subject to getting poisoned in mass to keep grass for the cows if they feel protected. Ask the coyotes or the wolves how they feel about getting trapped, shot, snared or poisoned because they sniffed the wrong carcass. Ask the sage hens if they feel they got a good deal at the hands of Sally Jewel and the cop-out GMO’s.

Don’t buy into this camouflaged desertification program.

All true re industrial livestock. Otherwise, you could not be more wrong. Do the research and google “desertification.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-deserts/desertification-threat-to-global-stability-u-n-study-idUSL272241020070628

Ask yourself why the droughts are so bad now in the Southwest. Get a global perspective and let go of your biases. There is hope, but not with narrow prejudices.

Down with industrial agriculture, only regenerative will heal the soils of the planet.

This is a very tough nut to crack. The die is cast for the foreseeable future. Take livestock off public lands for the best chance of positive ecological change, but 150 years of abuse has pretty much locked in the present condition. Alien weeds are a huge problem with no solution. The cheat grass/fire cycle is self perpetuating and nearly impossible to break. Soil loss over a century has robbed the semi arid lands of organic material, nutrients and water holding capacity. Wet meadows are no longer wet nor support abundant native vegetation. Creeks are mere conduits for water without rich riparian habitat to slow water and support wildlife and wildlife habitat anywhere near historic levels. Global warming is only making matters worse.

Sorry about the negative take, but the reality is we need drastic measures to gain even small improvements. Eliminating livestock from public lands should be the highest priority, but the western livestock lobby and Republican politics makes that a pipe dream at the present.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2021/11/12/busting-livestock-industry-myths-about-cattle-and-soil-carbon/

We can advocate until the cows come home. What we need is a concerted effort to buy out the ranches that have the best deeded BLM land and retire or reduce the cattle numbers.