The burnt-out Safeway Store in Paradise, California. Even a big parking lot with no fuel could not prevent the loss of this structure due to wind-blown embers. Photo George Wuerthner

A new report from Headwaters Economics titled: “Missing the Mark: Effectiveness and Funding in Community Wildfire Risk Reduction” misses the mark in many ways regarding wildfire issues.

I rely on Headwaters Economics for their good solid economic analysis, but when they stray into other areas, sometimes they, too, need to catch up.

In some ways, I hate to critique the report because there is much value in Missing the Mark report when they sick to home hardening and zoning issues, but the paper also supports what I consider misinformation about wildfire. They are heading in the right direction but frequently need help understanding the nuance of wildfire ecology.

The report has some critical and sound advice about home hardening and other effective ways of reducing the vulnerability of homes to wildfire. They argue that the Forest Service budget is disproportionally aimed at logging as a “solution” to wildfire.

As more and more homes are built in the Wildlands Urban Interface, we see more wildfires resulting from down power lines. Photo George Wuerthner

The central theme of their report is that federal dollars should be spent on assisting communities and homeowners to reduce the flammability of their homes, not logging the backcountry.

However, the report also champions more logging to reduce fires, using biomass burners to consume the wood from thinning projects. It fails to consider the collateral damage (including the economic costs) of current Forest Service management. It suggests that NEPA reform may be needed to “speed” logging projects.

Sanitized and degraded forest ecosystem resulting from thinning project on Deschutes National Forest, Oregon. Note the lack of ground cover, few snags, and no down wood on forest floor–usually found in healthy forest ecosystems. Photo George Wuerthner

One of the things I did immediately was to read the acknowledgments list of people interviewed. There was a firm reliance on pro-logging advocates and government officials from the research sector (almost all funded by the Forest Service) and Forest Service and state forestry employees.

I also reviewed the list of references, and again, they are overwhelmingly studies paid for and often written by agency scientists. I was surprised that few pf the referenced papers were by scientists who question the dominant paradigm.

Using members of the agencies as your major sources of information is as disingenuous as relying on the coal industry as an authority on climate change. Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

I also looked up the two authors’ backgrounds. Both have impressive resumes: Dr. Barrett’s research has focused on the true cost of wildfires, the cost of building wildfire-resistant homes, and measuring wildfire impacts through structure loss, while Dr. Dale from the Columbia University Climate School specializes in sustainability. They do an excellent job on those parts of the report.

Yet from what I can tell from their bios, they have little background or experience with wildfire/forest ecology and on-the-ground observations of the numerous failures of logging as a project prescription. This may explain why they support more harmful Forest Service activities like thinning and biomass burning.

The report focuses on reducing the risk of wildfire to communities, and in many ways, the information does an excellent job of advocating working from home outwards to reduce vulnerability to wildfires.

As the authors conclude: “the most effective policies for reducing community wildfire risk tend to be those that “manage the built environment, including mandated building codes and home hardening.” They note that such programs are underfunded, while efforts to suppress wildfires in wildlands get almost unlimited federal and state financial support.

This is a message that I and others have been harping upon for years, so it’s good to see that the Headwaters report confirms and emphasizes that theme.

Prescribed burning has limited applicability as a landscape influence on wildfire. Far too much emphasis is given to the notion that if we only did more prescribed burning we would not have large blazes. Wind-driven embers regularly fly over and around such “fuel reductions.” Photo George Wuerthner

However, a chart on page five points to prescribed burning as “highly effective” at protecting communities. That assertion is questionable for a host of reasons I have described elsewhere. But the chief reason is that wind-blown embers burn down homes.

Under extreme fire weather conditions, embers can be lofted several miles easily, flying over and around any prescribed burn effort. They acknowledge how embers are the main problem elsewhere in the paper but don’t always connect the dots. More on this later.

I was delighted to see the authors acknowledge the role of wildfire in ecosystems and that suppression is not conducive to effective fire management or ecosystem health. Furthermore, they note that climate change is the dominant force “fueling” larger blazes. On page nine, they have an entire paragraph on the numerous ecological benefits of wildfire.

The report notes: “So effective are these initial attack efforts that more than 99% of fires are suppressed before they exceed one acre in size. The large, damaging, and expensive fires that evade suppression make the news, but they represent a tiny fraction of the total.”

What the report fails to note (and what most fire authorities seem to miss) is that if you don’t have the right conditions for wildfire ignition and spread, wildfires self-extinguish without any suppression—usually burning less than 1 acre.

Graph showing wildfire acreage charred in Yellowstone NP. Note that long before there was “fire suppression” there were large blazes.

In other words, fire suppression isn’t that effective because the smaller fires may be put out by agencies, but the weather/climate largely controls the acreage charred. Even if firefighters left them alone, most would go out without human effort. On the other hand, when you have extreme fire weather, wildfires cannot be controlled.

And here is where the report starts to mimic Forest Service propaganda. “Without regular intervals of fire, many fire-dependent ecosystems become overly dense with woody biomass, creating flammable conditions that then contribute to more intense, larger wildfires when one inevitably escapes initial attack.”

Charred fir forest in the Bootleg Fire, Oregon. The vast majority of plant communities in the West tend to burn at mixed to high severity. Photo George Wuerthner

However, not all scientists agree that the frequent fire/low severity models apply to most plant communities in the West. A critical paper discussing fire ecology and, by implication, fire policy was published in the journal Fire.

The paper’s title: “Countering Omitted Evidence of Variable Historical Forests and Fire Regime in Western USA Dry Forests: The Low-Severity-Fire Model Rejected,” hints at the paper’s substance. The authors assert their research concludes that there is “a broad pattern of scientific misrepresentations and omissions by government forest and wildfire scientists.”

And this is where an understanding of ecology by someone with some wildfire ecology experience might have been helpful to the report. The authors repeat the misinterpretation of wildfire promoted by the timber industry, the Forest Service, and many FS researchers to justify human landscape manipulation.

While some ponderosa pine stands historically burned at frequent intervals that reduced fuels, and today have higher density and are burning more intensely than in the past, this does not apply to most plant communities in the West. Indeed, it doesn’t even apply to many ponderosa pine stands.

Nearly all the fire-dependent plant communities in the West, including aspen, sagebrush, juniper, fir, spruce, hemlocks, cedars, and even many pines, have very long intervals between wildfires of decades to centuries. They are not “overly dense” and naturally accumulate biomass over time, thus burning as “intense, large wildfires.” Even if it were practical, fire suppression has had little influence on these plant communities.

In other words, most wildfires in the West are burning at absolutely normal conditions under their ecological regimes.

While the authors, one of whom is a professor at the Columbia Climate School, acknowledge the role of current warming climate in fire spread, they need to recognize that climate has greatly influenced past wildfire occurrences.

Note the mid-century lack of large fires due to cool, moist climate conditions resulting from Pacific Decadal Osillation not fire suppresssion as commonly asserted.

Between the late 1930s, when the Forest Service initiated its 10 AM policy, and the more recent decades starting in the late 1980s, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation brought cool, moist conditions to the West. Glaciers were even growing in the Pacific Northwest at this time. And this is when the FS fire suppression was deemed “effective”.

Since the late 1980s, the climate has warmed considerably, and warmer temperatures, lower humidity, extensive drought, and high winds are the main factors contributing to large blazes, not fire suppression.

The long-term upward trend in temperature and vapor pressure deficit is also making droughts more severe, including the Western megadrought of the past 23 years, as hot and dry conditions pull more moisture from the landscape.

Dried up Lake Powell in Utah as a result of severe drought. Photo George Wuerthner

Given that many parts of the West are experiencing the most severe drought in a thousand years, it’s unsurprising that such severe droughts, combined with warmer temperatures, are the driving force in large blazes, not alleged fire suppression.

However, when they stick to economics, the report has much value. For instance, they note that 50-90% of federal firefighting dollars go towards protecting private homes. Rural governments continue to permit home construction in the Wildland Urban Interface, abd the authors note that these costs will increase. As they point out, these costs should be a private or state responsibility. But instead, all US taxpayers are subsidizing home construction in fire-prone areas.

To their credit, the authors discuss the Fire Industrial Complex, a topic covered at great length in my book Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy.

As the authors correctly note: “Institutional path dependency traps firefighting agencies in an endless pattern of buying new planes for aerial suppression, deploying those aircraft to fight fire even in unacceptably dangerous conditions, and feeding public expectations for ‘performative firefighting’ that may calm political nerves but ultimately fail to address the long-term threat wildfire poses to communities.”

One Forest Service official cynically noted that people love the “air show” even though most fires are nearly out when you can get planes dropping fire retardants.

The authors discuss “managed wildfire,” or allowing fires that do not pose a risk to homes to burn. One of the barriers they correctly identified is that promotion within the Forest Service and other agencies is based on “acres treated,” and managed wildfire does not count towards those totals. In other words, you get promoted if you log the forest but not if you allow wildfires to play their natural role in plant communities.

MISSING THE MARK

Headwaters Economics misses the mark the most in the part of the report on managing fires. The authors perpetuate the Industrial Forestry paradigm by suggesting: “Even in the absence of fire, reducing fuels may contribute to healthier forests and better habitat for wildlife.”

This ignores that what constitutes a “healthy” forest ecosystem is primarily based on timber industry ideas that limit mortality to chainsaw medicine.

Thinning and logging are ineffective at influencing wildfire under extreme fire weather. Here a thinned forest stand by Chester California did nothing to halt the 2021 wind-driven Dixie Fire. Photo George Wuerthner

Again demonstrating a poor understanding of wildfire behavior, the authors mimic the Forest Service in claiming that mechanical treatment (euphemism for logging) is effective at reducing large blazes. The authors contend that “Mechanical treatments are moderately effective at reducing fire severity, reducing the likelihood of crown fire, slowing the rate of spread, and moderating surface fire behavior.”

They don’t acknowledge the many qualifications that should accompany such a statement. The most important is that logging, prescribed burning, etc., have never worked at a landscape scale to reduce wildfires under wind-driven “extreme fire weather.”

If these authors had spent real time on the ground looking at large blazes across the West instead of relying on FS “research,” they would have noted that nearly all large fires burn through existing thinned and prescribed burn areas and that fuel treatment has failed repeatedly.

Area thinned “prior” to Millie Fire by Sisters, Oregon, did little to halt the blaze. It was a change in wind direction that “saved’ the town of Sisters. Photo George Wuerthner

When some logging advocates suggest otherwise, you must look at the fine print. For instance, the Deschutes National Forest regularly promotes the Millie Fire as an example of how thinning “saved” Sisters, Oregon, from wildfire. Even though the Millie Fire charred areas that had been thinned and burned through two previous wildfires, the agency claims that thinning halted the fire’s march toward Sister. However, if you look closely at the daily weather during the fire, a wind change drove the fire away from Sisters. This is frequently true when logging advocates suggest fuel reductions worked under extreme fire weather. (BTW, the agency has since removed the weather data on the Millie Fire from its website).

Map showing the pathway of the 2021 Holiday Farm Fire that burned down the McKenzie River in Oregon and Google Earth photo of clearcuts of the same area.

Another excellent example of how logging failed to protect communities was the Holiday Farm Fire which charred hundreds of thousands of acres along the McKenzie River in Oregon. The blaze raced through FS and industrial timber lands marked by clearcuts.

The Camp Fire burned through Paradise, California, despite the fact that the town was surrounded by clearcuts, previous “fuel reduction” logging, and several past blazes–all of which failed to prevent the loss of homes. Photo George Wuerthner

The same is true for the Camp Fire that consumed Paradise, the Dixie Fire that destroyed Greenville, California, and many other examples, I could give.

Why is this important? Because all large fires burn under such conditions. That logging may alter fire under low to moderate conditions is irrelevant, since most of these fires will burn out without any suppression, and they don’t burn hundreds of thousands of acres like wind-driven blazes.

Fortunately, the authors do recognize the inefficiency of fuel treatments. They report that the “influence of mechanical treatments on fire behavior is almost entirely ecological, short term, and localized.” They acknowledge that “Fuels-reduction projects can contribute to risk reduction in small, localized settings but do not offer a path to resolution of wildfire risk across the West.

But then one must wonder why to mention it at all.

Page 15 is one of the most troubling aspects of the report. Under barriers to “treatment” (they assume more fuel reductions is a good thing), they note that the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is a problem because it slows the agency’s logging agenda.

Like the libertarian Property and Environment Research Center (PERC), Senator Daines, and other logging proponents, they complain that: “Litigation itself can derail projects, adding additional delays to implementation or blocking them entirely. Instead of hiring foresters to treat fuels, land management agencies are forced to hire lawyers and analysts to navigate NEPA.”

Although they don’t specifically mention the Cottonwood Decision, they seem to condemn this as an unnecessary barrier because it requires NEPA analysis for thinning projects.

This is followed in the next segment by bemoaning that universities have shifted the emphasis of their programs as if this is a detrimental strategy. They say: “For example, many universities have re-configured their traditional forestry programs to meet better academic demand for popular but less forestry-focused environmental studies programs.”

This emphasis on speeding up logging implementation demonstrates that the authors haven’t thoroughly surveyed fire and ecological literature. If they did, they would recognize that in nearly all cases, logging has severe collateral environmental damage, including the spread of weeds, sediment in streams, disturbance to wildlife, impacts on water quality, loss of biomass (wildlife habitat to me), reduction in carbon storage, among others.

These are real ecological and economic costs of logging, and at the least, one would want the agencies to articulate these costs in a NEPA document.

The report goes on to repeat another myth. That logging the forest is profitable. Maybe for the timber companies subsidized in numerous economic and ecological ways, but certainly not for taxpayers. I unaware of any national forest in the country that makes a “profit” on timber sales—only the appearance of such because of false accounting, such as suggesting logging roads are a positive benefit because some people drive them for recreation or the failure to include all costs such the office rent, electrical power for computers, and the salaries of secretaries, other resource specialists, and personnel necessary to operate and implement a timber sale.

A report from Headwaters Economics should be aware of these accounting discrepancies.

TREATING THE HOME

Only when the authors focus on treating the home instead of the forest do they positively contribute to the fire discussion. As many have recognized for years, it is the treatment of the house that is both the most efficient and effective means of reducing home ignitions.

PRESCRIBED BURNING ADVOCATED

The report has a long section on prescribed burns, where fires are intentionally set under specific conditions that hopefully will not lead to a run-away blaze.

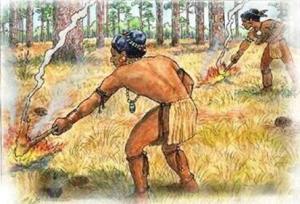

Research has shown that Indian burning had mostly localized influence on the landscape, and even with such activities there were always large blazes as a consequence of climate/weather.

Many officials, politicians, and journalists have latched on to Native American prescribe burning as the solution to major wildfires. Much of this is part of a social justice agenda that seeks to legitimize Native American cultural burning as a forgotten “wisdom” that “kept forests healthy and less fire-prone.

Without getting into this too much, the bottom line is that numerous studies have concluded that Indian burning was primarily localized and did not influence the larger landscape. Paleo fire evidence shows that large wildfires always existed despite tribal burns and that the climate then, as now, was the controlling factor in large blazes.

Snags from the 3 million acre plus 1910 “Big Burn” remain on a ridge line along the Idaho-Montana divide. No one can say that fire suppression created “excess” fuel for this blaze. Photo George Wuerthner

For instance, the 1910 “Big Burn” charred more than 3-3.5 million acres of Idaho and Montana long before anyone can suggest “fire suppression” had influenced fuels.

While advocating for a significant increase in prescribed burning, the authors themselves provide numerous reasons why this is not really a panacea.

They admit that such burns are typically localized and don’t affect the larger landscape. And they also note that many plant communities like sagebrush, juniper, and chaparral did not frequently burn. Thus, prescribed burns in these ecosystems are inappropriate.

An additional problem they acknowledge is that the most effective location for prescribed burns is adjacent to homes and communities. However, this often leads to public opposition due to fears that fires may escape and char structures.

Smoke is yet another issue since ideally prescribed burns are conducted when fuels are somewhat moist, leading to less than complete combustion, more smoke, and a higher percentage of particles that are unhealthy to breathe.

While smoke from a large wildfire may influence community members more, one must remember that most thinning and prescribed burn treatments never encounter a fire, so you wind up with the negatives like smoke without any benefits. Wildfire smoke travels hundreds of miles from the source, so even if you reduce fuels in the immediate area around the town, smoke may still impact the community as is now occurring in the eastern US as a result of Canadian wildfires.

It may be a reasonable gamble for most people to argue against repeated prescribed burns when the chances are nearly zero that a large wildfire will occur in that location.

In addition, prescribed burns may give homeowners a false sense of security. Given that most of all large blazes and home ignitions result from flying embers that are lofted over and around any fuel reduction treatment, it casts doubt that even a massive increase in prescribed burning will protect homes.

A final concern to a significant increase in prescribed burning is the narrow window for any controlled blaze. The fuel must be dry enough to ignite but not too dry to be explosive. You must consider factors like variability in the wind, which can blow up a burn into a major blaze.

One large wildfire consumes more biomass and affects far more acreage than thousands of prescribed burns. The focus on prescribed burning is a distraction. As one commentary explains, prescribed burning is like the watering can that pretends to be a hose-it simply will never influence enough landscape to make any significant difference in acreage burned.

Prescribed burning may have strategic value if done on a regular basis near homes and communities in high fire-risk areas, however, as a landscape scale strategy it is impractical and likely ineffecive.

This brings one back to the issue of the most effective and economical way to protect homes—managing the built environment and home hardening is the answer. And this is where the report is right on target.

A burning structure provides far more heat than a major wildfire. Wind-driven wildfires are like a tsunami. They offer a scorching but short tidal wave of heat. Most wooden walls can survive up to 20 minutes without ignition, and the house will survive if there is nothing adjacent to the home to ignite.

However, even if you harden your home to survive a wildfire, if your neighbor does not and their home ignites, the heat from a burning structure lasts longer and emits far more heat, often leading to the ignition of adjacent homes.

COMMUNITY STANDARDS NEEDED

Focusing on the home and town is one reason why community-wide fire-wise standards are critical. Zoning and construction with fire-resistant materials are among the most effective ways to reduce the cost of wildfire protection. For instance, in 2008, California mandated that all new homes be constructed with fire-resistant materials. A recent study found that new homes were 40% more likely to survive a blaze than older structures.

But as the authors correctly note, the idea of uniform building codes and standards is anathema in much of the rural West, where most vulnerable structures are located.

Funding for retrofitting homes is nearly nonexistent, even though such home hardening is the most effective and efficient means of reducing community vulnerability.

But even if hardened, homeowners must think outside of the box. The cause of home loss in one fire near Los Angeles was attributed to “doggie doors,” designed to swing open. During the windy conditions that characterize major blazes, embers could enter homes through these doors.

THEIR CONCLUSIONS

The report hits the mark and contributes to the wildfire policy discussion on issues related to community protection. The authors assert: “managing the built environment through home hardening and requiring those actions through robust and mandatory statewide building codes emerges here as by far the most effective tool for reducing wildfire risk.”

Their recommendations are for greater development of home hardening programs and for Congress to modify USFS budgets to support communities in implementing home hardening. The final recommendations for states and communities are right on the mark.

If you disregard most of the sections that promote thinning and burning as a strategy, the report has many worthwhile recommendations. I endorse the information with the above limitations.

Comments

An incredibly well-researched and comprehensive paper on the fire suppression fallacy. Excellent job, George.

Former US Forest Service Chief Mike Dombeck stated in the US Forest Service’s fire management publication, Fire Management Today, “Some argue that more commercial timber harvest is needed to remove small-diameter trees and brush that are fueling our worst wildlands fires in the interior West. However, small-diameter trees and brush typically have little or no commercial value. To offset losses from their removal, a commercial operator would have to remove large, merchantable trees in the overstory. Overstory removal lets more light reach the forest floor, promoting vigorous forest regeneration. Where the overstory has been entirely removed, regeneration produces thickets of 2,000 to 10,000 small trees per acre, precisely the small-diameter materials that are causing our worst fire problems. In fact, many large fires in 2000 burned in previously logged areas laced with roads. It seems unlikely that commercial timber harvest can solve our forest health problems” (Dombeck 2001).

The problem is that we shouldn’t be trying to suppress natural wildfires at all. We should be stopping all HUMAN-CAUSED fires, and closing some roads to allow forest regrowth. And we should make people who want to live in or near forests accept all the risks of doing so and fully responsible.